|

| Clifford Simak, older & wiser |

|

| Clifford Simak, young writer |

Grown men and women, sixty years old, twenty‑five years old, sit around and talk about the "golden age of science fiction," remembering when every story in every magazine was a masterwork of daring, original thought. Some say the golden age was circa 1928; some say 1939; some favor 1953, or 1970, or 1984. The arguments rage till the small of morning, and nothing is ever resolved. Because the real golden age of science fiction is twelve ....—Peter Graham

Twelve may be the golden age for science fiction but it started a bit earlier with me, and lasted a little longer, till at least my late forties, when I finally realized that whenever the golden age of science fiction was, it was certainly in the past, and the past is that which is forever lost. It was then that I looked at the state of modern science fiction and saw how little of it actually appealed to me -- comic book spin-offs, feminist fantasy, endless bland sequels of original novels that were bland to begin with, ideological and political treatises disguised as fiction, and tomes of jaded snarkiness written by clueless university graduates ensnared by cultural memes and tropes. I still read some science fiction these days, but, like me, it tends to be older, and just recently I re-read what may be the best science fiction novel ever written, though, technically, it's not a novel at all, but a collection of eight, sometimes nine, short stories.

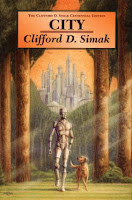

I first encountered City by Clifford Simak (1904 - 1988) in the very early 60s, in one of the many charity shops I frequented as a wayward youth looking for old books and magazines, squandering an allowance that can only be described as impecunious. It was the Ace paperback edition (D-283), published in 1958, featuring what was to my mind (then and now) the coolest robot ever (even better that those in Gold Key's Magus, Robot Fighter), painted by our pal Ed Valigursky, the uber-talented artist we've considered elsewhere in these pages. Very much an image of the 50s, with its knobs and dials, it's such a potent depiction that it was reused in later editions, or reworked to form similar covers for foreign printings. Of the 79 paintings Ed Valigursky did for Ace Books, this tops all of them. It sticks in the mind, and can even invade dreams. As good as this painting is, though, the story it illustrates is much better.

As mentioned earlier, it's not a novel proper, but a collection of stories (appearing in magazines from 1944 to 1951), which are tied together not just through theme and character, but via a preface and story notes written by the "editor," who is a dog. The beginning of the book is unforgettable:

"These are the stories that the Dogs tell when the fires burn high and the wind is from the north. Then each family circle gathers at the hearthstone and the pups sit silently and listen and when the story's done they ask many questions:

'What is Man?' they'll ask.

Or perhaps: 'What is a city?'

Or: 'What is a war?'"

In the publishing world, it's a fix-up novel, a book cobbled from shorter pieces published previously, something very common in the science fiction genre where the market for short stories was huge while the novel market was smaller than small, which is how such classic works as Asimov's Foundation series, Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, and many of A.E. Van Vogt's novels came about. The first story ("City") was published in the May 1944 issue of Astounding Science Fiction and tells of the decentralization of society and the abandonment of man's cities. Man's return to a pastoral life (this time because of the freedom brought by the use of unlimited energy generators) is a common theme in Simak's works, probably due to his rural Wisconsin upbringing, which would also account for his boundless love dogs; in City, they eventually become the dominant species, along with robots, but in most of Simak's novels there's usually a dog to be found tagging along somewhere. Dogs, robots and cities (or lack thereof) figure prominently in the covers of this well-loved book:

Personally, I think the French went a bit far with the dog angle when they retitled the book Demain les chiens, which translates as Tomorrow the Dog, but the French are French and there's just nothing to be done about it. If you want to find a copy of this book online, it's pretty easy, or if you live near a used book store (an endangered species if there ever was one); but you can also get a hardcover edition through the Science Fiction Book Club, which should include a ninth story written by Simak in 1973, which tells what eventually happens to the faithful robot Jenkins and the final fate of the ant-dominated Earth fled by man, dog and robot alike. For the purist (you're always out there somewhere, aren't you?), the original 1952 Gnome Press edition is usually available somewhere on AbeBooks or EBay.

All told, Clifford Simak wrote about thirty novels, along with numerous short story collections, but City is where I would advise the new reader to start. In it we see humanity and technology through Simak's pastoral eyes, and find robots and dogs who are better than the humans they serve. We also encounter such common Simak themes as souls, alternate timestreams, and pantropy. And we see why both editors and readers often termed Simak's human protagonists as "losers," men who usually muddled their way to success, and if they fell in love along the way it was as much accidental as incidental. "I like losers," Clifford Simak wrote, and he never abandoned his use of the lovable losers with whom we could all identify, no more than he did his beloved robots and dogs.

If you enjoyed this blog-post please feel free to share it with your friends using one of the social network buttons below. Thanks for investing your time, and for sharing.