|

| September 1962 |

When my mother broke her ankle many years ago, it fell to me to run errands for her, bring her glasses of water, make sandwiches, change channels (well, truth to tell, I had to do that anyway since children predate the invention of the remote), make meals, and a myriad of other services. My younger brother was always out running around with his ne'er-do-well cronies, so there never really was any thought of having him do any of the work...besides, it would have meant instilling a sense of responsibility. While taking care of my mother did not interfere with any outside activities it surely did cut into my reading. It seemed every time I picked up a book or magazine, my mother would ring her bell (how loud it was!) summoning me to bring or take away something. I prayed often for my mother's quick recuperation, and though my intentions were pure, I fear God would not have approved of my reasons.

Usually no good deed goes unpunished (or such was the axiom at my last place of employment), but this is not one of those instances. In a fit of gratitude, my mother said she would buy me any magazine I wanted from the rack at the local Thrifty Drug Store. I think she expected me to gravitate, as usual, to the comic books, which were only a dime. I probably would have -- Superman, Batman, Fantastic Four, Blackhawk, etc -- except I was suddenly distracted by a much smaller, though thicker publication, a digest-sized magazine entitled The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which cost a whopping 40 cents. Four times the cost of a comic, but she did say any magazine. She kept her word, but, then, she did not at the time know what I was getting myself into.

|

| May 1963 |

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF, as it is ubiquitously known) began in 1949, but I did not know anything about it. To me, it was as new as tomorrow, and the stories amazed me. While I had read fantasy and science fiction stories in anthologies, the existence of magazines filled with such fiction was unknown to me, which is odd, actually, because some of the anthologies were collections from the magazines themselves --I led a sheltered life, and sometimes failed to make obvious connections. I later branched off into the other magazines of the time -- Galaxy, Analog, If, Amazing, etc. -- but F&SF holds a special place in my literary heart.

One of the things I liked about F&SF was its special author issues, which were published on an irregular basis. Each one contained one or more stories by the featured author, a biography, a checklist of works, a commemorative cover and, usually, tributes by other writers. The first author for the honor was Theodore Sturgeon, a writer more known for short fiction than novels, in the September 1962 issue. The next author, in May 1963, was Ray Bradbury, another writer more known for his short fiction; his novel Fahrenheit 451 will never be equaled, though its lessons seem destined to be forgotten, time after time. I have a story to tell about Ray Bradbury, but the tale of Ray Bradbury, me and the tsunami will have to wait for another blog.

|

| October 1966 |

Now, of all the author issues, the Isaac Asimov special from 1966 was my favorite, for Asimov edged out Bradbury and even Arthur C. Clarke in my literary pantheon. I would not say I worshiped the man, but I probably did come a tad close to violating the first of the commandments brought down from the mountain by Moses. And this issue helped me get an "A+++" in an English class, the only such grade ever awarded by Mrs Wells.

We had to write an essay on our favorite writer, and my choice was Isaac Asimov, someone not known to Mrs Wells...but she qualified as an expert by the time she finished my entry. We had to write 8-10 pages, and that meant by hand -- back then, not every kid could afford a typewriter. We had only pens, pencils and our brains, and I think we outperformed the modern breed of gadget-addicted savants. While our teacher specified the number of pages, she failed to mention not to use legal-length paper and she had no idea a human could print so damned small. My paper was easily three times longer than the efforts of my fellow academicians. She was more careful when it came to future assignments.

|

| April 1971 |

|

| July 1969 |

I also enjoyed the F&SF issues honoring Fritz Leiber (l) and Poul Anderson (r). I had the great pleasure of meeting Leiber at a World Fantasy Convention in the 90s; and Anderson had the misfortune of having his house invaded by myself and my cousin during a school vacation. Both writers are no longer with us, but one thing about being a writer is that you never really depart this world, not while people still read your stories and think of you. My memories of Leiber and Anderson are still as vivid as they were in my youth, perhaps even more so because fondness for departed friends always seems to grow even as the sadness at their passing seems to ebb.

F&SF continued publishing special author issues through the 1970s, honoring James Blish (April 1972), Frederick Pohl (September 1973), Robert Silverberg (April 1974), Damon Knight (November 1976) and Harlan Ellison (July 1977), most of whom I had the chance to meet at one time or another at various events

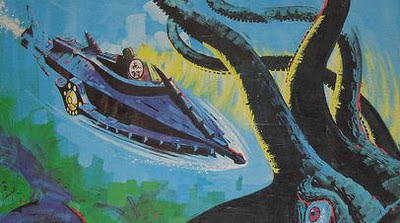

I always associate James Blish with flying cities, an epic series of novels which first appeared in Astounding during the war years, which were given a new level of popularity by another generation in the 1960s, then again in the 1980s. Over the years, I've read a bunch of Frederick Pohl's novels (as well as his collaborations with C.M. Kornbluth), but none of them really stand out as having affected me or changed my outlook; he is a "series writer," is that his novels generally fall into one of his many highly popular literary universes. Reading Robert Silverberg's tales is to be immersed in a world of mythic proportions, and he's one of the first writers to assault readers with the club of social conscience. Time travel, drugs, religion, sex, race and social turmoil -- all are grist for the grindstones of his cosmic mill.

Damon Knight was a prolific writer, but if he is known for one thing, it will be for a story called "To Serve Man." Even those who never read it are familiar with it thanks to it being adapted as a episode of the original Twilight Zone. Despite the story being simplified almost to the point of butchery, no one will ever forget the last line about the book (To Serve Man) left by the aliens -- "It's a cook book!" The ironic twist was Knight's signature and why his short fiction is more powerful than it would be just for its themes and concepts.

Harlan Ellison was an attendee at the same fantasy convention at which I met Leiber, Silverberg and others, and he was the hardest working person there, attending panel after panel, often leaving one panel halfway through so he could make it to another, or showing up late. He brought it on himself because he asked the organizers to schedule him for as many panels as humanly possible...as it turned out, they scheduled him for as many as was inhumanly possible, but, unbelievably, he coped with the demand on his time and intellect. None of it really surprised me because he writes the same way -- breakneck speed, meteor-impact intensity and knowledgeable of subjects as far apart as life and death. Most fans, writers, editors and publishers (and James Cameron) have horror stories to tell about the "enfant terrible of science fiction," but I saw him at his best and most gracious, unshaken by the demands of that wonderful week.

After a long hiatus F&SF published five more special author issues, beginning with Stephen King in December 1990 and ending with Gene Wolf in April 2007, but they are not in my collection. I had changed by then, developing other interests, pursuing other activities; and economic realities had also changed for me. Money that I might have otherwise spent on necessities like books and magazines was diverted to such luxuries as a mortgage, children's education and food on the table. The world is an eminently unfair place, especially to those whose life is an open book.