I don't know about you, but I'm rather disappointed with the way our Solar System turned out. It's totally changed from the way it was when I was a lad. Not only have the planets gotten extreme makeovers, but we don't even have nine planets anymore, Pluto having been given the boot by some narrow-minded astro-boffins; any day now, I expect poor little Mercury to get a pink slip: "Sorry, Mercury, don't get all hot under the collar, but you're just too small to play with us...go whine to Pluto and all the other asteroids."

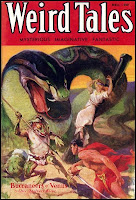

As recently as the 1970s (I know, some of you were not even born then, but that's not my fault) our Solar System was a place of mystery and adventure, the planets not very different than they were to the pulp writers of the previous generations, who set stories in the mines of Mercury, the jungles of Venus and the canals of Mars. Modern science has ripped away the mystery of those other worlds, not only taking away the hopes for grand adventures, but making the planets, to me at least, much less interesting. You can still read the old stories by Ray Cummings and Leigh Brackett, Arthur C Clarke and Otis Adelbert Kline, or Jack Williamson and H.P. Lovecraft, but the adventure is always tempered with a measure of wistful sadness, for now they are not science fiction stories of possible (if not probable) futures, but fables or fairy tales, and while we can still derive pleasure from them, it is not an enjoyment seasoned with anticipation. I like the classic view of the planets, so when I sat down to write Shadows Against the Empire, I set the action not in the Solar System as it is, but in the Solar System as it should have been, an alternate universe where old school astronomy still ruled.

The big thing about classic Mercury is that it is (or should be) tidally locked, as is our Moon, one side ever facing the sun. The planet being in such a situation creates stable climates on both sides of the planet, one metal-melting hot, the other cold as absolute zero, both of which can be endured and exploited; more than that, however, tidal-locked Mercury has a kind of temperate band between the two extremes, a "twilight zone" where colonies can be built. Isaac Asimov (writing as Paul French) sent his protagonists onto the hot half of Mercury in Lucky Starr & the Big Sun of Mercury, as did Alan E. Nourse with "Brightside Crossing." Writer Leigh Brackett located her cities in the Twilight Zone, and had two of her main protagonists, Eric John Stark and Jaffa Storm, born there. Two writers who took on non-human inhabitants of Mercury were Arthur C. Clarke, who described a Dark Side creature in Islands in the Sky, and Hal Clement, who wrote about the Bright Side's silicon occupants in Iceworld. During the 19th Century, astronomers observed a planet even closer to the sun than Mercury and called it Vulcan, but no one ever wrote about it...oh, the planet with the pointy-eared chaps? Sorry, not the same one.

Venus was always fun to speculate about, if only because our wild guesses about what lay beneath its thick cloud cover were just as valid as those of the astro-boffins with their big telescopes. Swamps, lizard men, jungles, tempestuous oceans, trackless deserts and soaring mountains, torrential rains that made Seattle look parched, and ancient cities connected by rivers dwarfing the Nile and Amazon. Anything went because no one could penetrate those clouds. And then came that terrible day when all us Venus theorizing space cadets found ourselves in the same position as Professor Harold Hill:

Marcellus Washburn: I heard you was in steam automobiles.

Professor Harold Hill: I was... till someone actually 'invented' one!

Not only did they use radar to tell us what the planet looked like under the thick canopy of roiling clouds but those darned Soviets actually landed a probe on Venus -- it melted. So much for jungles, swamps, oceans and even the poor old lizard-men. It was no tropic paradise as Ray Bradbury and H.P. Lovecraft had promised in two of their stories. Nor could we sail our schooners around the seas of Venus to encounter pirates and sea monsters as Edgar Rice Burroughs had assured us in the adventures of wrong-way astronaut Carson Napier in the Amtor (as the natives called Venus) Series, and as ERB wannabe Otis Adelbert Kline wrote in Prince of Peril and Port of Peril. No longer could China colonize Venus for the purpose of cultivating rice, as it did in Jack Williamson's Seetee Ship. Even the dark and dangerous cities visited by Northwest Smith, where segir (Venusian whisky) is cheap and life cheaper, went up in a poof of sulfurous smoke. In an instant, Venus went from Planet Mystery to Planet Hell. Thanks, Russia.

Of all the planets to transition from the "old" Solar System to the "new," Mars was perhaps the hardest hit, if only because everyone expected so much out of it. It wasn't just that we thought it might be the abode of life, we knew it. Even though we had never seen cities there, had never actually seen the blue waters of the canals, and had never received any signals from the Martians, we knew they were waiting for us...or coming to get us, as the case may be. In the Nineteenth Century a cash prize was offered to anyone who could prove life existed on another planet...except Mars. Burroughs populated it with all manner of creatures and ancient races, making it even more interesting than Earth. So did Ray Bradbury, C.L. Moore and Robert Heinlein; theologian and sometimes SF writer C.S. Lewis made Mars the abode of angelic beings in Out of the Silent Planet. As more information was gathered about Mars, the canals, the cities, the thin but breathable atmosphere...all went the way of dreams at the dawning. Some writers struggled on, but most sighed, grabbed the latest copies of Scientific American and Astronomy, and plotted new stories that did not depend upon Martians. A final farewell, a sort of eulogy, was published by F&SF in its November 1963 issue, A Rose for Ecclesiastes by Roger Zelazny.

I don't claim that good adventure stories cannot be written in the Solar System as it now exists, for I have read many over the years, but I do claim that the "new" astronomy put an end to the planetary adventure tale as it existed for more two centuries. Now, anyone who wants to set stories on the inhabited planets of our Solar System must either use human colonists, life-forms with which we can little contact, or establish an alternate universe where things went differently, as many steampunk writers (and me) have done. Otherwise, writers looking for adventures that involve swashbuckling or derring-do must either travel to Earth's past or seek new worlds out amongst the stars.

Of course, that does not mean our neighboring planet is entirely bereft of surprises...

|

| So were Chinese Crested dogs. |

|

| Please, no carping about this one |

|

| Like this surprises anyone! |

|

| Obviously, he took the better offer. |

No comments:

Post a Comment